We’re like nothing else in the world

Dr. Joseph LeBlanc on social justice in medical education, what NOSM University is getting right on that score—and what he says has to happen next.

The Associate Dean of Equity and Inclusion at NOSM University is frank, unfazed and unequivocal: it’s long past time to draw the line on racism in health care—and it starts with medical education and research.

“We have to create an environment where acts of racism are consistently and appropriately confronted,” says Dr. Joseph LeBlanc, “and future health professionals are taught to address systemic challenges caused by racism and colonialism.”

As of 2020, Dr. LeBlanc is the first person to be appointed to his inaugural portfolio, which was created to help promote equity, increase diversity, and strengthen the culture of inclusion among faculty, staff, learners and alumni.

His mandate covers everything from anti-racist policy-making to addressing Francophone language rights in health-care education and accessiblity, to amplifying issues around sexism, ableism and LGBTQQ2S+ rights.

“We ultimately created this portfolio to address some very serious and pervasive health-care injustices in the North and beyond,” says Dr. Sarita Verma, President, Vice Chancellor, Dean and CEO of NOSM University.

“We know that racialized and other marginalized people have a harder time accessing safe and competent health care,” she continues. “We know that people of colour, especially women, are more likely to live in poverty and face more stigma as a result. This is real life. NOSM University works hard to make sure that every doctor we graduate is acutely aware of the health inequities currently baked into the system, and is a compassionate care provider who will lead with—and model—an attitude of social justice. That is what defines us as a university.”

Dr. LeBlanc applauds the groundbreaking efforts made by NOSM University to date. “NOSM University has made space for diverse academic leadership and participation. For example, he says, nowhere else has a Chair in the History of Indigenous Health and Traditional Medicine.”

“We’ve also established the Academic Indigenous Health Education Committee (AIHEC),” Dr. LeBlanc continues. “It was established as part of the University’s Academic Council [now the University Senate], which is so crucial; it’s a seat and a voice at the head table when it comes to what and how learners are taught with respect to Indigenous health education.”

“We also now offer an Indigenous Peoples’ Health and Wellness Collaborative Specialization, and it’s the first of its kind in Canada. The first eight medical students enrolled have just finished their first year, which is incredible.”

“We’re like nothing else in the world,” he says. “But, if we were completely equitable,” Dr. LeBlanc posits, “we wouldn’t need an equity strategy.”

Equity Strategy

Dr. LeBlanc and his colleagues are defining that new strategy, and he says that both philosophically and in concrete terms, the plan will mark a significant systemic shift.

“The current winds are actually blowing away from ‘Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI)’ into anti-racism,” he explains. “I want us to move into decolonization and anti-racism.”

Terms

Active Offer: “the overt and active offer of health services in French… the regular and permanent offer of services to the Francophone population” as required by Ontario’s French Language Services Act.

Anti-racism: “The active process of identifying and eliminating racism by changing systems, organizational structures, policies and practices and attitudes, so that power is redistributed and shared equitably.”

Colonialism: “Colonialism in Canada may be best understood as Indigenous peoples’ forced disconnection from land, culture and community by another group.” Also: “The policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another [place], occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.”

Cultural Safety: “An outcome based on respectful engagement that recognizes and strives to address power imbalances inherent in the health care system. It results in an environment free of racism and discrimination, where people feel safe when receiving health care.”

Decolonisation: “Once viewed as the formal process of handing over the instruments of government, is now recognized as a long-term process involving the bureaucratic, cultural, linguistic and psychological divesting [and active rejection] of colonial power.”

Equity: “‘Equity’ is the fair and respectful treatment of all people and involves the creation of opportunities and reduction of disparities in opportunities and outcomes for diverse communities. It also acknowledges that these disparities are rooted in historical and contemporary injustices and disadvantages.”

On the continuum of becoming truly anti-racist, Dr. LeBlanc says an EDI approach is a step in the right direction, but doesn’t often “make waves” or actually require the necessary work to become fully inclusive.

He says that in practice, becoming an overtly, intentionally anti-racist institution will be unsettling to some people: it’s a direct and open rebuke of a white-centered, colonialist worldview and its corollary—endemic, institutionalized white privilege.

For example, in a fully transformed educational institution, Dr. LeBlanc believes that admissions wouldn’t focus on diversity numbers so much as see diversity as an “institutionalized asset” that helps to “restore a sense of community and mutual caring.”

“That’s very different from, ‘Let’s find admission targets that we’re comfortable with.”

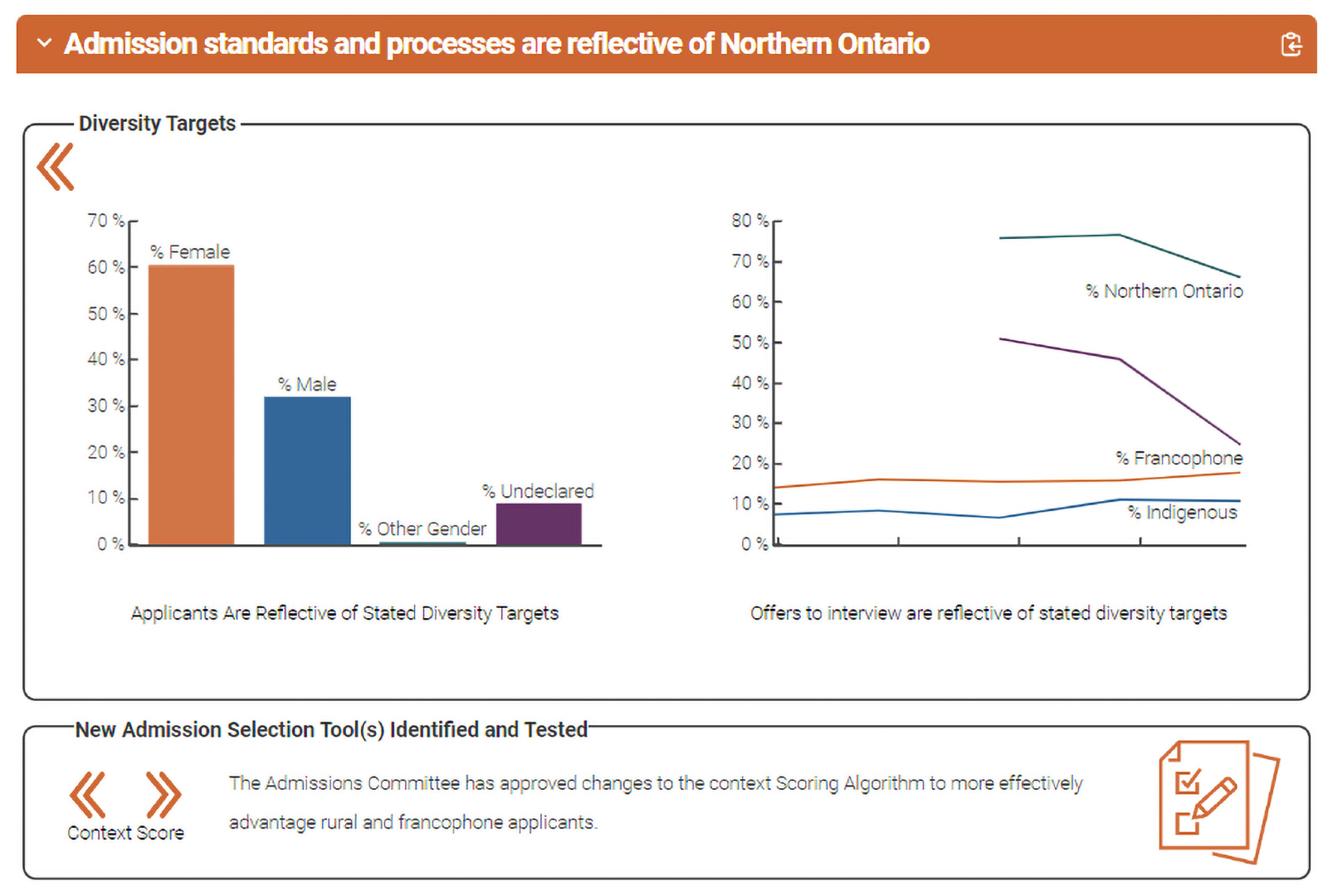

Dr. LeBlanc acknowledges that NOSM University’s diverse admissions goals are important to advancing social accountability as part of its current strategic plan. At the same time, he wants to see an updated overhaul to the admissions process through an anti-racist, anti-colonial, radically inclusive lens.

“There is an open door for Indigenous students to NOSM University,” he says. “Look at the percentages: we’re at 17 per cent again in this class, and our goal is to have 20 per cent of each MD class be Indigenous. But it’s about more than numbers. We need to have a good look at ourselves—and the curriculum—and do the hard work of changing.”

The ‘Front Door’

Dr. LeBlanc likens the admissions process to NOSM University’s “front door,” and says that the admissions team must be among those empowered to “red flag” applicants who don’t meet new criteria, or fail to demonstrate an anti-racist attitude and understanding of the University’s social justice mandate.

“With an anti-racist shift,” he says, “now we look at the rest of the class. Who are they? Are they racist? And is there any evidence that we can remediate racism? There isn’t.”

“So what does a decolonial, anti-racist school, do?” he continues. “It is required to look at 100 per cent of the class and consider what is their aptitude towards anti-racism and decolonization.”

“Often I think admissions thinks about, ‘Who’s going to complete the course? Who’s going to do well in the courses?’

“No,” says Dr. LeBlanc. “The question should be, ‘Who’s gonna do harm in the world?’”

“This ‘house’,” he continues, “values Indigenous Cultural Safety (ICS) training and Active Offer to the point that we’re not going to expect you to do it sometime while you’re here.”

“Next year, we are requiring all incoming medical students to submit one of three ICS certificates and the Active Offer at the same time as they submit their vaccinations and First Aid certificate.”

“This is a big one,” he says. “If you don’t want to take three hours to learn about French language service rights as a health provider in Northern Ontario… that’s a major problem.”

Dr. LeBlanc says future NOSM University applicants can also expect a social media scan and a mandatory Professionalism Agreement upon entry.

“That is explicitly related to racism and explicitly related to sexism and ableism and other things,” he says. “So if, in the future, you do something like make a post in a Facebook group that cuts down Muslim students, for example, you can expect consequences for those actions.”

‘Actionism’

An important philosophical piece of the vision laid out by Dr. LeBlanc and his colleagues is instilling an attitude of “actionism” into future physicians.

NOSM University-trained doctors are taught about the importance of physician advocacy, and that is an important element of doing what’s right in the service of social justice, says Dr. LeBlanc.

“But whereas activist advocacy—perhaps standing up in front of a microphone and using the weight of your white coat to ask the public and government for support for a cause or health issue—is a professional competency, the actionist advocate position instead asks doctors to assume direct ownership over what they can change,” he says.

For example, he continues, “Actionism is, you’re a doctor in a remote community, and you get to know the people running the community garden. You say to them, ‘Hey, I’m flying back in an empty plane—can I bring anything back that would help you or the garden?’”

“Taking action—being an actionist advocate—in this example will help people in the community to have a better garden, perhaps, and that will help them to be healthier overall. Isn’t that the role of a doctor? To help people be healthy? In the current construct of what defines a physician, doing something like this would never be captured in the metrics. But that’s what an actionist does.”

Moving Forward

Dr. LeBlanc presented the Equity Strategy to the Board in December 2021. Aside from the recommendations on recruitment and admissions, Dr. LeBlanc and his colleagues advise that there are three other areas upon which the University must be “laser-focused” with an anti-racist bent: curricular development, advocacy and public education, and research.

Dr. LeBlanc notes that the Board accepted the recommendations in full, and that much of the work outlined in the plan is already underway.

As for NOSM University’s official buy-in, it’s “all systems go.”

In its motion to approve, the Board writes, “The University must ensure equity initiatives are treated as a high priority in future priority-based budgeting actions,” and “NOSM University must engage in a continual process of self-reflection, and ensure that this commitment is enshrined.”

“NOSM University will do the work to become a fully transformed institution,” says Dr. Verma. “It’s already in our DNA. There is no harm in critically examining the systems that define an institution; to the contrary, there can be great harm in not doing so.”

“I see these recommendations as directives,” she adds. “It is no longer about ‘aspiring’ to be fully inclusive. It’s about getting there.”